By Nick Butler

Tags: Other

This post gives practical guidance on building closer relationships with your audience through clear copyright information on your digital channels. It pulls together lessons from three NDF 2019 talks on copyright for digital GLAMs.

It’s based on the idea that the best copyright information makes it easy for people to use the works in your collections. It tells users what they can do, not just what they can’t. Doing this has clear benefits in areas like public engagement, collection access, outreach and marketing.

By digital GLAMs, we mean Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums who share their collections online.

The talks were part of the 2019 National Digital Forum conference, held at Te Papa in Wellington, New Zealand. You can watch them on YouTube.

The three topics covered are:

They look at copyright for digital GLAMs from three perspectives:

The post ends with a summary of the lessons from the three talks.

While this survey tries to keep things simple, there are complex issues surrounding copyright for digital GLAMs. One presenter, for example, shared this excerpt of Victoria Leachman’s 10 page Te Papa copyright duration flowchart (subtitled A Copyright Flowchart of Death).

Working out Copyright for Te Papa’s Collection. Flowchart by Victoria Leachman https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2008-1827 © Te Papa, 2019

Slidedeck (PDF)

Michael Lascarides, the UX manager at New Zealand’s National Library, ran through the work they’ve done to create easy-to-use rights statements on DigitalNZ.

DigitalNZ’s mission is to make New Zealand’s cultural heritage easy to find, share, and use. Using a digital collection aggregation tool, the DigitalNZ website pulls together over 30 million items — photos, videos, news stories and more — from over 200 content partners.

To make it easy to use these treasures, DigitalNZ need to clearly explain how people can use them. Otherwise people might misuse items or, worse, mistakenly think they were not allowed to use items that in fact they can.

The team wanted rights statements — the messages that sit alongside individual items in a collection, explaining its copyright status — that answered one question:

How can I use this thing?

For DigitalNZ, this is not always clear. As an aggregator of other people’s content, DigitalNZ is rarely the rights holder.

“So we need to walk the line between making solid statements about use, while making it clear that the ultimate call about usage rights rests with the rights holder, not us,” says Michael.

But what they’ve learned about communicating rights is relevant to other GLAM institutions. Indeed, they’re keen to take their learnings to related properties, like the National Library website and Papers Past.

DigitalNZ rely on what their content partners tell them, via each item’s metadata, about its rights status. They pull three rights fields from partners:

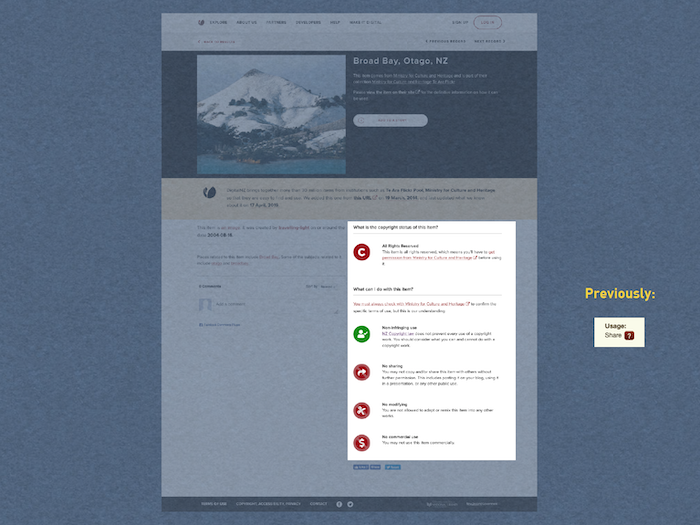

Until 2017, the only rights help they gave alongside each item was the Usage value and a tooltip on a slightly uncertain-looking question mark.

The tool tip said: “Before copying or reusing any item found on DigitalNZ, you need to check the terms of use and/or copyright on the item’s web page. Click on ‘?’ for more about these usage filters.”

Clicking the ? took you to a page on “Reusing items found on DigitalNZ” (here’s the Internet Archive version).

User testing showed this confused people. So they tried tailoring the messages more to what they knew about the item: the usage and rights_url fields.

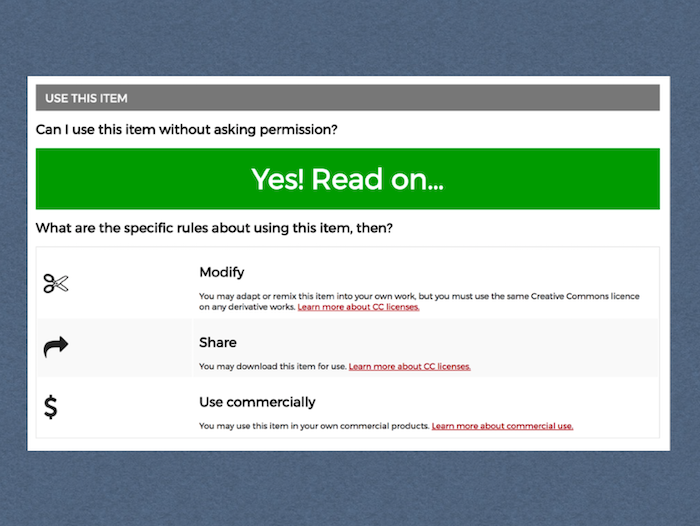

For example, where the rights_url field gave a Creative Commons license, they could show something like this:

Feedback from user testing was positive about the Q&A approach. However, too many items would get not a “Yes! Read on…” but rather a “Possibly” or a “Yes, but”.

So the next iteration featured a specific copyright statement, including detail pulled from any Creative Commons license. The “What can do with this item?” element included the caveat that DigitalNZ needed as an aggregator: “You must check with the copyright holder”. There’s also a section on what you can do with any item, based on fair dealing provisions.

More iterations followed. The emphasis was on using layout, icons and user-centred plain language to be as clear and specific as possible, while still keeping content partners and lawyers happy.

They went live with something like this:

And the feedback from real users in their 2019 DigitalNZ Satisfaction Survey was positive: “I find it extremely clear how you deal with rights usage for items and greatly appreciate this.”

Michael shared 4 lessons from this work:

Even for “All rights reserved” materials, there is always something you are allowed to do with them. So why not explain what these things are.

Sometimes less is less. Clarity is the goal, and brevity is just one tool in achieving this.

The new approach revealed cases where the rights metadata was contradictory. This shows it’s important to have consistent information about the rights of your items.

Comparing what they have now with what they had previously below shows the gains you can get from an Agile, iterative approach:

One way DigitalNZ were able to be more specific, was by leveraging Creative Commons licenses. So let’s look at them now.

Creative Commons copyright licensing explained — YouTube

On behalf of Victoria Leachman, Catriona McPherson presented an introduction to Creative Commons, prompted by questions from previous NDF conferences.

Creative Commons are a standardised set of 6 copyright licenses.

CC licenses travel with the work that’s been licensed. Victoria describes it as being like a bus pass. So if you use an item that has a CC license, you need to note that license near the item. To make that easy, you can convey them in set of simple abbreviations and symbols that you can read at a glance.

The 6 licenses are built out of 4 elements:

| Attribution | BY | |

| NonCommercial | NC | |

| NoDerivs | ND | |

| ShareAlike | SA | |

Icons by Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0)

Here’s what these mean:

Credit the creator. All CC licenses require attribution.

You can’t use the work if you’re collecting money in return for reproducing the item. This can be a grey area. If you’re in doubt, put yourself in the creator’s shoes.

You can use the work but you can’t change, adapt or remix it.

If you change or remix the work, you have to include the same license.

Here are the six licences:

These licenses sit on a spectrum, as shown in the graphic below. They run from most open at the top to the most restrictive at the bottom.

Creative commons license spectrum by Shaddim, original CC license symbols by Creative Commons, (CC BY 4.0)

PD, or public domain, is the most open because there is no copyright. It’s either expired or never existed. Importantly, you can’t apply a CC licence to a work in the public domain.

Content creators can also waive copyright via CC0.

At the other end of the spectrum are works with All rights reserved. But this doesn’t mean you can’t use the work. It just means you have to get permission from the copyright owner to do so.

Only the copyright owner or administrator can apply copyright. And owning the physical work doesn’t necessarily make you the copyright owner. So you need to know if you or your institution own the copyright before applying a Creative Commons license.

Always:

If the specific Creative Commons license on an item doesn’t work for you, go back and ask. Copyright owners can always give you permission to do more.

So what does the work that GLAM institutions do to clarify copyright mean for users? In particular, what does it mean for people wanting to use works in the public domain?

Giz it: A journey in reuse — YouTube

Mike Dickison presented this talk on behalf of Siobhan Leachman. Siobhan describes herself as a digital GLAM enthusiast and wikimedian. She collates and curates GLAM content via Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata. She’s basically a GLAM superuser.

Siobhan shared a bunch of ways GLAMs can make it easier for people wanting to reuse public domain content (or its digital surrogates).

Siobhan started by saying how much she appreciates the amazing work done by people in the GLAM sector. She also said she makes no claims to being a copyright expert.

Her talk was premised on the idea that GLAMs hold public domain content in trust. New Zealanders create, collect and donate these works. They support the GLAM sector through taxes, rates, grants, fees and donations of time and money. For Siobhan, this means that culturally-appropriate, public domain digital content should be freely reusable.

Doing this helps GLAMs achieve their goals. These include things like changing hearts and minds, connecting through sharing stories, serving communities, co-creating knowledge and enriching lives.

So what are some ways they can they do this?

Siobhan suggests you:

She also suggests letting people search specifically for works that are in the public domain. This makes the copyright status of these works clear.

Think of all the terms of use pages you might have. For example, you might have an overall website terms and conditions page, download or reproduction terms, and statements on individual items. Make these consistent.

In particular, avoid blanket restrictions that limit the use of public domain works. This includes restrictions that are part of:

Where restrictions are due to cultural sensitivities, apply these to individual works.

As Victoria Leachman explained, public domain works cannot have any copyright license, including a Creative Commons license.

This is important because, as Michael Lascarides noted, these Creative Commons licenses get pulled through by aggregators like DigitalNZ. So this adds to the confusion.

Siobhan suggests GLAM institutions should invest in education about the public domain and what it means for copyright and reuse. She sees this as starting at the top, with the board and CEO.

You can sum up the combined lessons from the three talks like this:

DigitalNZ guidance on usage rights for digital content

Te Papa’s guide to Copyright and Museums (PDF)

Victoria Leachman’s Te Papa copyright duration flowchart (Google Doc)

Ministry of Business Innovation & Employment copyright guidance

New Zealand Intellectual Property office copyright guidance

Sharing digital collections: Guide for galleries, libraries, archives and museums — Helping people enjoy your treasures

Accessible digital services for the cultural heritage sector — Harnessing accessibility to achieve your outcomes

Co-design case study — Developing a digital heritage portal for and with the people of the Pacific

DigitalNZ cloud migration case study — Moving GLAM collection applications to the cloud

Papers Past digital archive — Creating an easy-to-search digital archive revolutionises research in New Zealand

Top image credit: Copyright Books by Casey Fiesler (cropped) – licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0