By Nick Butler

Tags: Agile , Development

In this post, we look at how Agile transparency reduces project risk, especially risks to the quality and value of your product.

Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

William O. DouglasA lack of transparency results in distrust and a deep sense of insecurity.

Dalai Lama

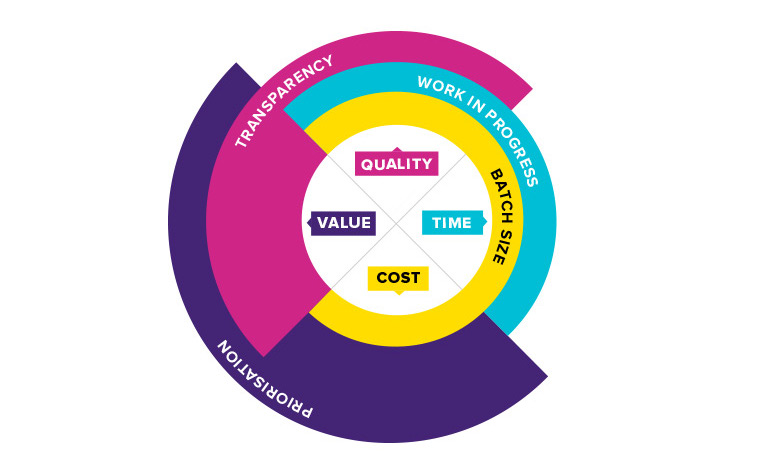

In our post on reducing software development risk with Agile prioritisation, we saw that there are four key Agile approaches for managing risk: prioritisation, transparency, batch size and work in progress. Each approach reduces one or more of the most common software development risks — risks around quality, time, cost and value.

Get your complete guide to

Project risk management with Agile

Increasing transparency reduces the risk of producing work of poor quality and low value. Put simply, without transparency, we cannot manage risk.

Lack of transparency leads to poor quality, which has a strong negative impact on an organisation’s brand and revenue.

Customers delay sales and you lose revenue because of poor quality. Releasing poor quality software builds the expectation that initial releases will be buggy. If a release date slips several times, new and potential customers may assume there is a problem with quality and will be reluctant to buy when the software is finally released. Even a single sub-par release can sow the seeds of doubt. Once doubt creeps into the minds of existing customers, they may delay purchasing new releases, preferring to allow other early adopters to work through the problems, or worse, they may decide not to buy.

Even if we deliver the necessary quality, without transparency, we run the risk of ‘achieving failure’: delivering a product that the market neither needs or wants.

Transparency, as used in science, engineering, business, the humanities and in a social context more generally, implies openness, communication, and accountability. Transparency is operating in such a way that it is easy for others to see what actions are performed.

Transparency is about making obvious the reasons we are doing the work, the way we are doing the work, the quality of the work and functionality of the work.

When we talk about transparency it is very easy to see it in only one dimension. Often we will focus on the dimension that is most relevant or pressing in our role. For example, a manager may see transparency as knowing the status of the work. For a developer, transparency may be about seeing the work in progress in a tool or on a task board. Increasing transparency in all aspects of the work we do delivers the highest benefit and reduces project risk across the board.

Agile transparency builds on the Agile values. These favour individuals and interactions over processes and tools, working software over comprehensive documentation, customer collaboration over contract negotiation, and responding to change over following a plan.

In Scrum, one of the most popular frameworks for Agile, transparency is one of the three pillars, along with inspection and adaptation. Extreme Programming, another popular framework, builds in transparency via the values of communication and feedback and the practice of creating an informative workspace.

We cover some practical Agile transparency tools below.

Transparency enables us to make good decisions.

A simple example is the Scrum task-board. The board shows, to anyone who walks past it, what’s being worked on, what’s complete, what’s in progress and what remains to be started.

This transparency enables the team to see, at a glance, whether they are on track to meet their sprint goal, have too much work in progress or are blocked on one or more stories.

The team can use this information to change the way they are working. If the team sees that too much work is in progress, they can decide to focus on the most important story until it is complete before moving on to the next story.

Without transparency around processes and output, the team is unable to make informed decisions. When the team is unable to make good decisions, they will not be able to deliver value and quality to their customers.

Fill in the table below to see how your project or organisation is doing with transparency.

Download your printable transparency evaluation checklist (PDF)

| Practice | Yes/No |

| All team members know why they are working on the project | |

| All team members have an explicit and shared understanding of ‘quality’ | |

| The output of my teams is frequently and regularly inspected | |

| The processes we use are frequently and regularly inspected | |

| The work of the team is visible to the team | |

| The work of the team is visible to the organisation | |

| Individuals are empowered to raise issues and red flags | |

| All team members have an explicit and shared understanding of when work is complete |

Add up one point for every question to which you answered ‘yes’.

0-2 points: There is little transparency in your teams.

3-6 points: While there is some visibility of the work and processes, there are a number of opportunities for improvement.

7-8 points: You’re transparent (like a jellyfish!) – nice work.

Most Agile teams use some form of information radiator to reveal project progress.

Start by setting up a white-board (dry-erase board) in the space where your team works. 150cm by 120cm is a good size. The columns on your board should represent the stages your work items go through as they progress from start to finish.

Below is a sketch of a basic Kanban-style board. The work moves from unstarted at the left of the board to the finished column on the right side.

In this example, work is moved to the In Progress column once it starts and then to the Testing column before moving into Finished. The columns with blue backgrounds represent a state where work is happening. For the work to flow smoothly, work can wait in buffers before moving to the next work state. The buffers are the columns with a yellow background: Ready, and Ready to Test.

Implementing a Kanban board like the one in our example takes only a small amount of time but you will quickly see where there are bottlenecks or other issues.

Tip: It’s best to start with just dry-erase markers on a dry-erase board. This makes it much easier to make changes to the board as you learn and adjust your processes.

We look at Kanban boards again in our posts on work in progress and batch size. This case study explores using a big visible information radiator to communicate the state of a complex system.

While less obvious than information radiators, Scrum meetings are just as important in creating transparency.

Sprint planning makes transparent the work that needs to be done and why. Sprint planning also encourages the team to share assumptions and ideas. Estimation, whether included in sprint planning or scheduled as a separate meeting, provides another layer of information and involves team members (including the Product Owner) in sharing their assumptions, knowledge and work scope.

Sprint reviews inspect the work done in the current sprint or iteration. Great sprint reviews welcome not only the team and stakeholders but the wider organisation (and sometimes others). Progress (or lack of it), quality and decisions made are reviewed and shared, giving the whole organisation a view into the team. This level of transparency ensures projects are held accountable for the work they are doing and do not drift off track.

The sprint retrospective – another Scrum meeting – is an excellent way for the team to gain insight into the way they are working, the technology and their relationship with the wider organisation. Great retrospectives produce actions for the team to take to improve their productivity and the quality of their work.

Unfortunately, they are a sadly neglected part of the Scrum framework and are often repetitive and dull. Retro after retro, teams provide the same answers to the same questions. It doesn’t have to be this way.

If you are just starting out, we recommend the 5 step retros described by Esther Derby and Dianna Larsen in Agile Retrospectives: Making Good Teams Great.

Here are the 5 steps from Agile Retrospectives: Making Good Teams Great:

Other resources that will help you get the most out of retrospectives are:

Retrospectives are most valuable when they are well-facilitated. The facilitator should ensure that everyone’s voice is heard. Techniques such as silent brainstorming can work well to gather a divergent set of views. It’s also important that the whole team is involved. If you are a Scrum team, it can be useful to have the Product Owner there too.

Retrospectives rely on a high level of commitment and respect. Without trust and respect we are at risk of creating a blame culture which is a strong disincentive to transparency. It can take teams some time to develop the empathy and trust needed for truly deep retrospection on their work as a team.

Tip: Working within the framework described in Agile Retrospectives, you can begin to create your own. Our Retrospective ideas blog post collects a number that we’ve created at Boost.

The more we know about our processes and output, and the quality and value of what we are producing, the more we reduce project risk. Agile transparency enables us to react quickly. The more information we have, the quicker and more informed our response will be to changing circumstances.

An example of how transparency reduces project risk is the case of technical debt. We know that technical debt is very costly, soaking up time and resource if defects are not caught early. In one study by IBM, it was found that:

the cost of fixing defects increases exponentially as software progresses through the development lifecycle, [therefore] it’s critical to catch defects as early as possible. The costs of discovering defects after release are significant: up to 30 times more than if you catch them in the design and architectural phase…

Many projects get to a point where adding a feature in one place breaks something seemingly unrelated in another part of the project. By the time technical debt becomes apparent in a project, we’ve usually acquired a lot of it.

We can think of a project’s codebase as a garden. One approach is to invest 100% of our effort into planting new plants, constantly turning over new ground and expanding our garden. This works for a while, but not for long. Within a short while the plants we first planted are beginning to be strangled by weeds, perhaps they are growing wildly in their own right. We soon learn to apportion some of our time to maintaining what we have already planted in order to get the most value from the earlier work.

If we can see the maintenance work that needs to be completed, we can resource and manage it. If we can’t examine this technical debt, we will see systemic problems appear. By discouraging the team from being transparent about the quality of the project, we create these un-maintained, un-maintainable gardens.

Being concerned about quality (maintaining existing code) over progress (advancing new work) does not lead to teams being less productive or delivering less value. The key is to find the balance. We need to make our needs around quality transparent – for example, using documents such as the “Definition of Done” to make quality explicit – and then inspect and talk about our work regularly.

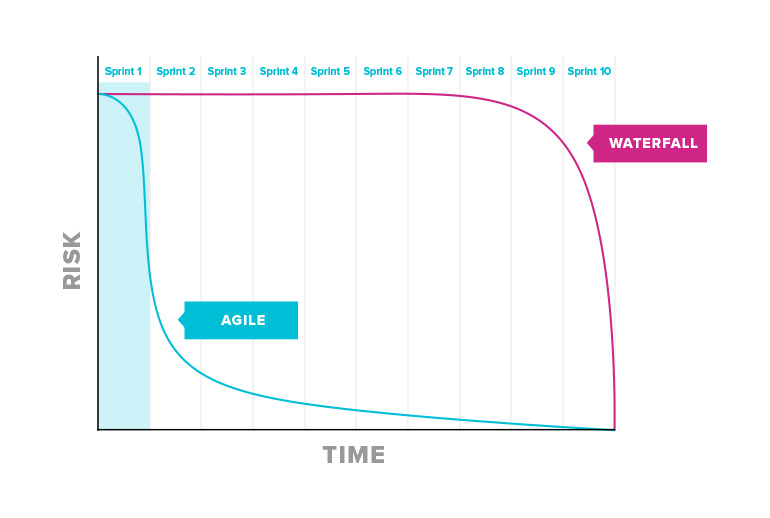

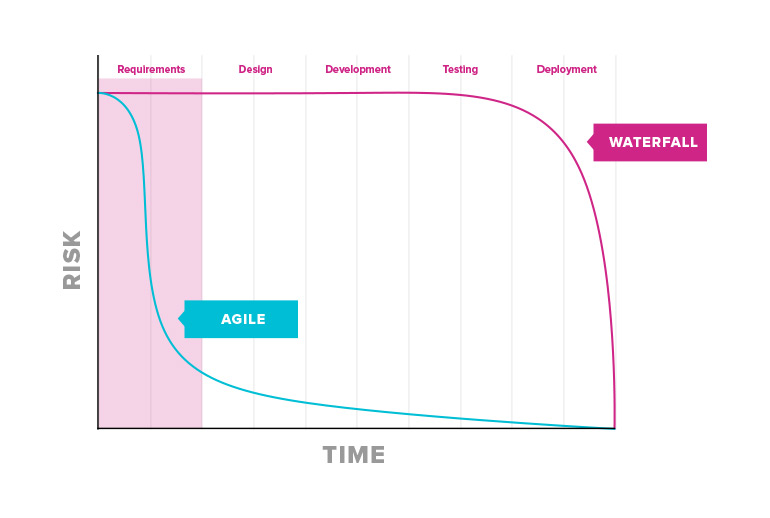

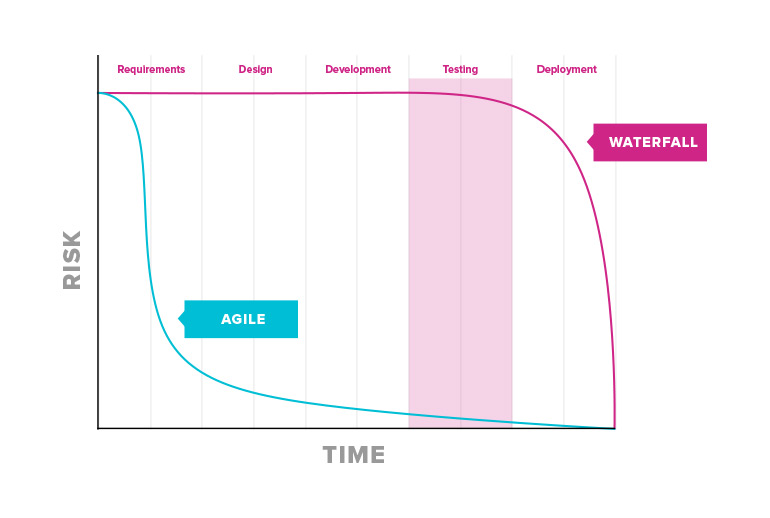

The graph below depicts a simplified risk profile for an Agile project compared with a Waterfall project.

The following assumptions are made for the sake of simplicity. In the Agile project, the sprints are two weeks long. In the Waterfall project, each stage is four weeks long. Both projects go according to plan and achieve an optimum result over the same time period. Both projects deliver the same value, in the same time, with the same resource.

Let’s look at how much risk is carried through the project and why. In the graph below we can see the first time that we get any visibility into the Agile project is after the first sprint. At the sprint review at the end of sprint 1, anyone can see the working software produced. There is potentially shippable software of some value. We can inspect the quality of the work. We can assess security. And we can test with real users whether the features delivered offer value. If the project stops at this point there has been some value produced. Risk starts to decrease.

In the Waterfall project, the first real visibility we get into the project is at the end of the requirements phase. Often at this stage the requirements will be shared with the wider project team and be reviewed as part of the project governance. While we have some visibility into what has been produced so far, we don’t have any view of the value of the work, how appropriate it is for our audience or whether it will be of high quality. Should the project stop now, we will have nothing of value (where value is determined by the end users). Risk remains very high.

It is not until the testing phase that the risk in the Waterfall project starts to fall. This is the first time that we get to inspect the quality of the product in earnest.

It is not until the testing phase that the risk in the Waterfall project starts to fall. This is the first time that we get to inspect the quality of the product in earnest.

By the same time in the Agile project we have delivered six sprints (12 weeks in this example) of working tested code. We have 60% of the functionality 100% completed. This is in contrast with the Waterfall project where we have 100% of the functionality 60% complete.

It is worth noting that the functionality completed in the Agile project would be the most valuable functionality. This means that we already have more than 60% of the value. Looking at the example outlined in the IntuitionHQ case study, it may be that by this stage of the project we may have delivered enough value to stop the project or take a step back and reprioritise.

As transparency increases in your organisation you will encounter issues that were not previously visible. You may uncover blocks to the team’s work in the wider organisation or management approaches that have not yet adapted to Agile ways of working. It may appear that transparency has ’caused’ the problems and is, therefore, a problem in its own right.

For example a team beginning to use Scrum will find their productivity is much more visible to the organisation. Productivity may not be any lower than before the team used Scrum (usually it is higher), but it is very visible. The organisation around the team may conclude that productivity has dropped, if they had previously made an assumption that it was highly productive. The conclusion that the organisation draws is that Scrum causes a drop in productivity, rather than that Scrum is more transparent about productivity.

Increased transparency decreases risk by laying bare what is actually going on in our projects. It gives us the opportunity to address previously unclear or hidden issues and respond quickly and effectively to new ones.

We cannot have high quality or high value without high transparency. The cost of low quality in dollars, reputation and brand damage is huge. The cost of ‘achieving failure’ – delivering something that the customer neither wants or needs – is devastating.

When we are transparent, we are no longer wishfully thinking that following the plan is delivering value and decreasing project risk. Instead, we are using information from the team and the market to improve quality and increase value to the organisation and the customer.

| Guidance | Case studies & resources |

|---|---|

| Introduction to project risk management with Agile | Agile risk management checklist — check and tune your practice |

| Effective prioritisation | |

| Reduce software development risk with Agile prioritisation | Reducing risk with Agile prioritisation: IntuitionHQ case study |

| Increasing transparency | |

| How Agile transparency reduces project risk | Risk transparency: Smells, Meteors & Upgrades Board case study |

| Limiting work in progress | |

| Manage project risk by limiting work in progress | Reducing WIP to limit risk: Blocked stories case study |

| Reducing batch size | |

| How to reduce batch size in Agile software development | Reducing batch size to manage risk: Story splitting case study |